- Home

- James L. Swanson

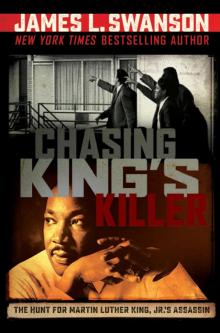

Chasing King's Killer Page 2

Chasing King's Killer Read online

Page 2

Once Izola Curry was in custody, every word she spoke to police officers or reporters confirmed the initial impression that she was mentally disturbed, rather than a conspirator. During her arraignment hearing in court the day after the stabbing, the magistrate observed her behavior and declared, “This woman is ill.”

“I am not ill,” Curry objected.

When the magistrate said, “I understand that this is the woman who is accused of stabbing the Reverend Dr. King with a knife,” Curry corrected him and shouted, “No! It was a letter opener,” as if that had made her attack any less dangerous.

From his hospital bed, King asked that this troubled woman not be punished. “I feel no ill-will toward [her] and know that thoughtful people will do all in their power to see that she gets the help she apparently needs.” Charged with attempted murder, Curry was never put on trial. Instead, she was sent to a mental institution.

On October 3, King was released from Harlem Hospital and, after a month of rest and recuperation, made a full recovery. It seemed he was destined for more.

If Izola Curry had murdered Martin Luther King, Jr., on September 20, 1958, his assassination would have reshaped the arc of history and the destiny of twentieth-century America.

It is amazing how the actions of one anonymous person can change the future of not only a great person but an entire nation.

King’s death would have created a void. Eloquent words would never have been spoken, great deeds would have gone undone, and grievous wrongs might not have been righted. Without Dr. King, the civil rights movement might have been thwarted, delayed, or gone in a different direction. Luck—destiny—God had spared him that day. He would live.

But the assassination attempt changed Martin Luther King, Jr. It reinforced in him a sense of fatalism, an acceptance of the dangers, risks, and uncertainty that he must make his peace with if he chose to continue to lead the civil rights movement. “The experience of these last few days has deepened my faith in the … spirit of nonviolence,” he said. “I have now come to see more clearly [its] redemptive power.”

A less courageous man might have been tempted to quit the movement and seek a safe and quiet life. But not King. As he said after the stabbing, “We must all be prepared to die.” Strangely, King’s surgical scars healed in the form of a cross over his heart. He joked that these were appropriate wounds for a minister of the gospel.

When Martin Luther King, Jr., arose from his hospital sickbed in the fall of 1958, he could not have imagined the future that awaited him. He was about to embark on an inspiring, decade-long journey that would lift him to the pinnacle of a symbolic mountaintop and make him one of the most pivotal leaders of the twentieth century. His greatest days lay ahead of him. He would become more than the champion of a great civil rights cause. For millions of people in the United States and around the world, he would become its beloved living, breathing symbol.

No, in September 1958, twenty-nine-year-old Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., knew none of this …

Martin Luther King, Jr., was born in Atlanta, Georgia, on January 15, 1929.

As he would learn, it was not easy to be black in early twentieth-century America. Even though the Civil War had ended in 1865, just sixty-four years before King’s birth, African Americans still did not enjoy equal rights under the law. That war may have ended slavery, but generations later, black Americans were neither free nor equal citizens.

In the South, the states of the old Confederacy enacted so-called “Jim Crow” laws to strip black people of their civil rights. These unjust laws were based on the white supremacist belief that blacks were an inferior race. Racism was entrenched by the very institutions that were supposed to protect the rights of all citizens. Instead, these laws explicitly discriminated against blacks by creating “whites only” schools, theaters, hotels, restaurants, and other public accommodations. Blacks were not allowed to live in the same neighborhoods as whites, to attend state universities, or even to drink from the same water fountains. Throughout the South, signs reading WHITE and COLORED marked the boundaries of a segregated society.

Blacks were not allowed to exercise their political rights, either. Voter registration was suppressed, elections were rigged, and black candidates found it difficult to get on the ballot to run for office. They had little political power.

In the South, the state officials—the governors and mayors—were white, and so were the federal officeholders—the U.S. congressmen and senators.

The justice system was also unfair. In criminal trials, white judges and all-white juries often convicted—and even sentenced to death—black defendants on the flimsiest of evidence.

Through legal restrictions, whites controlled all aspects of blacks’ lives: their rights, their movements in public, their activities, and their very bodies. This was accomplished not just through a system of racist laws and the power of the state. Intimidation, violence, and murder were essential tools in the suppression of African Americans. The Ku Klux Klan, a notorious racist terrorist organization whose symbol, a burning cross, subjected Southern blacks to horrific and senseless assaults. Local law enforcement—policemen and sheriffs—sometimes took part in these atrocious attacks, and some of them were even members of the Klan.

Between the late 1800s and the 1920s, over 3,200 black people had been lynched in America, mostly in the South. Sometimes white mobs broke into jails and hanged men who were awaiting trial. On other occasions, whites abducted blacks from the streets, the roads, or their own homes and hanged them for no reason at all, other than to create fear and reinforce white supremacy. There were even examples of lynch mobs degenerating into public celebrations, with photographers taking gruesome souvenir photos of victims that were later sold as postcards.

Racism was not only a Southern phenomenon. It existed in the North, too, where it was less blatant and obvious. And Northerners were not above racist violence. In 1908, rioting whites murdered blacks in Springfield, Illinois, Abraham Lincoln’s hometown, and in Chicago in 1919.

Segregation also hurt blacks economically. Denied jobs, opportunities, and good wages because of their race, many blacks suffered in poverty and were not much better off than they had been during slavery. Without good schools or an education, there was no clear path to get ahead. Abraham Lincoln once compared slavery to a hopeless prison in which blacks were jailed behind a cell door locked with one hundred keys, making it impossible ever to escape. In the South, segregation and Jim Crow laws had kept African Americans in a similar prison ever since the Civil War.

This was the world into which Martin Luther King, Jr., was born. And the time had come for change.

Martin Luther King, Jr., was the son of the prominent pastor of Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church. During his earliest years, Martin’s parents shielded him from the ugliest realities of racism.

Martin was raised as a member of the black elite. His family’s status was based on their community service and religious leadership, not wealth. The King family was never poor, nor were they rich. Martin described his neighbors as people of average income. It was, he said, a “wholesome” community where crime was minimal and most people were deeply religious.

Martin joined the church when he was five. His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all preachers, and so was his uncle. Religion was a natural and important part of his life, and he attended church every Sunday.

He never suffered hunger or deprivation. “I have never experienced the feeling of not having the basic necessities of life. These things were always provided by my father, who always put his family first.” Young Martin never had to drop out of school to work to earn money for the family. Looking back on his youth, he recalled: “The first twenty-five years of my life were very comfortable years. If I had a problem I could always call Daddy … Life had been wrapped up for me in a Christmas package.”

Martin was a precocious child who possessed an inborn curiosity and a love of books and learning. One day his mother

, Alberta, the daughter of a prominent minister, decided that Martin was old enough to hear what black parents today still call “The Talk”: the conversation to prepare a black child for the racism he might -encounter in the outside world. Martin never forgot it.

“My mother confronted the age-old problem of the Negro parent in America: how to explain discrimination and segregation to a small child … She told me about slavery, and how it ended with the Civil War. She tried to explain the divided system of the South—the segregated schools, restaurants, theaters, housing; the white and colored signs on drinking fountains, waiting rooms, lavatories— as a social condition rather than a natural order.” Martin’s mother said that she opposed these racist practices and told him that he must never allow them to make him feel inferior. “You are as good as anyone,” she taught her firstborn son. But as much as his parents protected him from racism, he never forgot his early childhood encounters with segregation.

When Martin was six, a white boy who had been his playmate since they were three years old ended their friendship when he went to a white, segregated school. It crushed Martin, who admitted, “from that moment on I was determined to hate every white person.” His parents admonished him that he should not hate.

Once when Martin’s father took him to a shoe store, the salesman said that they would have to get up from their seats and move to the back of the store. His father, the elder Reverend King, got up and walked out: “We’ll either buy shoes sitting here, or we won’t buy shoes at all.”

Martin suffered segregation at parks, swimming pools, schools, and movie theaters. One day when he was eight years old, his mother took him shopping in downtown Atlanta. A white woman slapped him in the face and spoke a vile insult: “You are that ‘n*****’ that stepped on my foot.” That word, now considered so offensive that many books and newspapers will no longer print it, was once a common slur that whites used when speaking to or talking about blacks.

Martin remembered the time in high school when a white bus driver ordered him and a female teacher to give up their seats to white people—“it was the angriest I have ever been in my life”—and he remembered when a white policeman dared to call his father, one of the most distinguished men in Atlanta, “boy.” It was a word meant to show disrespect to black men.

The summer before Martin started college, he went to Connecticut to work on a tobacco farm. The experience had a profound effect on him. He was treated as an equal of the young white local teens who worked with him in the fields. There were no WHITES ONLY signs on water fountains or soda machines. He could go to restaurants. And he could sit wherever he liked in theaters or buses or trains. He relished the temporary freedom from segregation that he enjoyed in the North. In sharp contrast, returning home to the Southern system depressed him. “I could never adjust to the separate waiting rooms, separate eating places, separate restrooms, partly because the separate was always unequal, and partly because the very idea of separation did something to my sense of dignity and self-respect.”

In 1944, during the Second World War, Martin enrolled at the unusually young age of fifteen as a freshman at Morehouse College, a prominent black institution that both his father and his mother’s father had attended. Martin already had a strong interest in racial and economic justice, but on campus he experienced an intellectual awakening when he read Henry David Thoreau’s famous essay “Civil Disobedience.” It was King’s first exposure to the theory of nonviolent resistance. “Fascinated by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system, I was so deeply moved that I reread the work several times. I became convinced that noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good.”

In his senior year in college, before he had even graduated, Martin followed family tradition and was ordained at Ebenezer Baptist Church as a minister in February 1948. After graduating that June at age nineteen, he entered Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania for advanced religious training. In the spring of 1950, he experienced a second intellectual awakening when he traveled to Philadelphia to hear a sermon by Dr. Mordecai Johnson. Johnson was the president of Howard University, a famous black school in Washington, DC. The educator spoke about the leader of the Indian independence movement, Mohandas Gandhi. India had been a former colony of the British Empire, achieving independence only after the Second World War. Martin found Gandhi’s philosophy of peaceful resistance to Great Britain’s control over India “profound and electrifying.”

In the fall of 1951, Martin entered Boston University’s School of Theology to earn a doctorate degree. The next year he met a young woman named Coretta Scott. She had attended Antioch College in Ohio and was a student at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. A talented musician who wanted to be a concert singer, her physical beauty and intellectual nature proved impossible for Martin to resist. Martin and Coretta married in June 1953.

As a preacher’s wife, Coretta was expected to support Martin’s ministry and give up her dreams of travel and a glamorous career as a professional singer. Later in life, Martin acknowledged the sacrifices that “Corrie” had made. “She had to settle down to a few concerts here and there. Basically she has been a pastor’s wife and mother of our four children.” In September 1954, Martin became the pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Nine months later, he received his PhD in theology and earned the right to be called doctor. After that, many of his closest associates would call him Doc. He joined the local branch of the NAACP (the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). And in November 1955, his and Coretta’s first child, a daughter, was born.

In the fall of 1955, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was headed for a predictable, quiet life as a minister, husband, father, and respected local community leader. He seemed content to follow in his father’s footsteps. He had no ambitions to become famous, to seek political office, or to become the leader of a national movement. If he had stayed on this path, it is possible that no one living outside Montgomery, Alabama, would have ever heard of Martin Luther King, Jr.

But before the end of the year, something happened that upended his life and set him on a new course.

On December 1, 1955, a woman named Rosa Parks was arrested in Montgomery for violating the city’s bus segregation law when she refused to give up her seat to a white passenger. Black leaders had been looking for an opportunity to challenge the law. A few days later, they elected Martin Luther King, Jr., as the head of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). It was a new organization, and they wanted Martin to lead the campaign.

King and his colleagues decided that if blacks could not ride the buses of Montgomery as equal citizens, they would not ride them at all. To stay in business, the bus company depended on the fares paid by black passengers. If blacks boycotted the buses, the company’s income would plummet. But African Americans needed the buses to get to and from work. So the MIA organized carpools. Many people walked. Some people even rode on horseback or in wagons or mule carts. And many white people volunteered to drive their maids, cooks, and nannies to work.

It was not long before segregationists fought back with violence. On January 30, 1956, while Martin spoke at a meeting to support the bus boycott, his home was bombed. He was not there when it happened, but it was a frightening warning of what some whites were willing to do to resist civil rights. The bombing also made it clear that not only King but also his family were in danger.

The boycott lasted for about one year. It was a hardship, but it united the black community. On November 13, 1956, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the Montgomery, Alabama, bus segregation laws violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution’s guarantee of equal treatment under the law.

The next month, the MIA voted to end the boycott. King was one of the first people to ride a desegregated bus, on which blacks would no longer have to sit in the back. In addition, no longer would they have to surrender their seats to white people.

After everything that King and the movement had endured to fight for those rights, the day of victory was anticlimactic. The white bus driver wished King good morning, welcomed him aboard, and proceeded on his route as though nothing out of the ordinary had just happened.

But something extraordinary had happened to Martin Luther King, Jr. His leadership during the Montgomery bus boycott had made him famous. In May 1957, he was invited to speak in Washington, DC, at the Lincoln Memorial for an event called a Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom.

King’s portrait even appeared on the cover of Time magazine, a sign that the most influential news magazine in America had decided he was of national importance. It was an honor that few blacks had ever received.

And King had been elected president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. It was a new organization that would soon become one of the most important groups in the nation advocating for the civil rights of black Americans.

Martin Luther King, Jr., was a rising star. But then, on September 20, 1958, he was stabbed by Izola Curry. The injuries threatened to end King’s life at the dawn of a brilliant career.

He had two choices—he could heed his close call with death, step out of the spotlight, and return to his quiet life. Or he could continue his work. He chose to recommit himself to the civil rights movement.

King realized that if he hoped to change history, he needed a grand strategy. It would not be enough to hold a few scattered and random boycotts and protests. King was realistic about what he was up against and the power of the system he opposed. In 1958, the civil rights movement faced a formidable task: overcoming the effects of a regime of slavery that had existed for two and a half centuries, from the early 1600s to 1865, the end of the Civil War. In addition, there was the unbearable injustice that had existed since 1865. The crushing oppression of 350 years could not be reversed overnight. It would take time. Great patience and many victories and setbacks would be required. It had taken a long time to abolish slavery. Similarly, King and the civil rights movement needed a long-term plan, a multipart strategy. But the regime King hoped to defeat would not surrender its power easily.

Bloody Times: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Manhunt for Jefferson Davis

Bloody Times: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Manhunt for Jefferson Davis Bloody Crimes: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Chase for Jefferson Davis

Bloody Crimes: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Chase for Jefferson Davis Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer

Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer Chasing King's Killer: The Hunt for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Assassin

Chasing King's Killer: The Hunt for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Assassin Bloody Crimes

Bloody Crimes End of Days

End of Days Chasing Lincoln's Killer

Chasing Lincoln's Killer Bloody Times

Bloody Times Manhunt

Manhunt Chasing King's Killer

Chasing King's Killer