- Home

- James L. Swanson

Chasing Lincoln's Killer

Chasing Lincoln's Killer Read online

This story is true. All the characters are real and were alive during the great manhunt of April 1865. Their words are authentic. In fact, all text appearing within quotation marks comes from original sources: letters, manuscripts, trial transcripts, newspapers, government reports, pamphlets, books, and other documents. What happened in Washington, D.C., in the spring of 1865, and in the swamps and rivers, forests and fields of Maryland and Virginia during the following twelve days, is far too incredible to have been made up.

I was born on February 12, Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, and my fascination with our sixteenth president began when I was a young boy. On my tenth birthday, my grandmother gave me an unusual present: an engraving of the Deringer pistol John Wilkes Booth used to assassinate Abraham Lincoln, framed by a newspaper article (on page 17) published on the day after the assassination. The newspaper article described some aspects of the assassination, but was cut off before the end of the story. I knew I had to find the rest of the story. This book is my way of doing that.

The author as a boy

THE PRESIDENT AND HIS FAMILY

Abraham Lincoln

Mary Todd Lincoln

Robert Todd Lincoln

Thomas “Tad” Lincoln

GUESTS OF THE LINCOLNS AT FORD’S THEATRE

Major Henry Rathbone

Clara Harris

PRINCIPAL CABINET MEMBERS

Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton

Secretary of State William H. Seward

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles

PRINCIPAL DOCTORS

Dr. Charles A. Leale

Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes

CONFEDERATE LEADERS

President Jefferson Davis

General Robert E. Lee

CONSPIRATORS

John Wilkes Booth

David Herold

Lewis Powell

George Atzerodt

Mary Surratt

John Harrison Surratt

Dr. Samuel A. Mudd

PRINCIPAL ACCOMPLICES

Thomas Jones

Captain Samuel Cox

PRINCIPAL MANHUNTERS

Lieutenant Edward P. Doherty

Luther Byron Baker

Colonel Lafayette Baker

Colonel Everton Conger

Lieutenant David Dana

Sergeant Boston Corbett

the United States endured a bloody civil war between Northern and Southern states. The conflict had begun long before over the right to own slaves and states’ right to secede, that is, to leave the Union if they disagreed with the government.

In the North, where the economy was based on factories and industry, most citizens considered slavery brutal, inhuman, and immoral. In the South, where the economy was dependent on slave labor, citizens believed they should have the right to own slaves. They also believed that if the national government disagreed with that right, Southern states had the right to secede.

Lincoln, elected president of the United States in 1860 just before the outbreak of the Civil War, held two strong beliefs: that slavery was morally wrong, and that the North and South must remain united as one country.

Southern soldiers, dressed in gray uniforms, were called rebels and Confederates. Northern soldiers, dressed in navy blue uniforms, were referred to as Union soldiers or Yankees.

The war lasted four years and resulted in more than 600,000 casualties, half of them lost to disease. After several bloody battles and costly, prolonged campaigns, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginiato Union General Ulysses S. Grant in the Virginia town of Appomattox Court House. But other rebel armies continued fighting in the field. Lee’s surrender did not mean the end of the war or of danger. Some Confederate sympathizers mourned the outcome of the war — the “lost cause” — would forever change the Southern way of life, including slavery. Many Southerners were unwilling to give up the lost cause, believing they could continue to fight and eventually win, or die trying. It was a dangerous place and time. With Lee’s surrender, soldiers shed their uniforms, turned in their weapons, and rode or walked home to resume their lives. Spies and Confederate sympathizers as well as soldiers filled the Union capital, Washington, D.C. People could not tell based on clothing, geography, or appearance which side of the conflict people supported.

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

INTRODUCTION

LIST OF MAJOR PARTICIPANTS

FROM 1861 THROUGH 1865

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV: TRIAL AND EXECUTION

EPILOGUE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ROUTE OF THE ASSASSINS

COPYRIGHT

It looked like a bad day for photographers. Terrible winds and thunderstorms had swept through Washington early that morning, dissolving the dirt streets into a sticky muck of soil and garbage. The ugly gray sky of the morning of March 4, 1865, threatened to spoil the great day. Photographer William M. Smith was to take a historic photograph of the presidential inauguration in front of the recently completed Capitol dome. Smith framed the view from the marble statue of George Washington on the lawn to the top of the dome, crowned by a statue of Freedom. Abraham Lincoln had ordered work on building the Capitol dome to continue during the war as a sign that the Union would go on.

Closer to the Capitol, Alexander Gardner set up his camera to photograph the inauguration. Gardner captured not only images of the president, vice president, chief justice, and other honored guests occupying the stands, but also the anonymous faces of hundreds of spectators who crowded the east front of the Capitol. In one photograph, on a balcony above the stands, a young man with a black mustache and wearing a top hat gazes down on the president. It is the famous actor John Wilkes Booth.

(Previous page) Perhaps the finest portrait of John Wilkes Booth ever made, this magnificent large-format photograph remains vivid evidence of Booth’s appeal.

Abraham Lincoln rose from his chair and walked toward the podium. He was now at the height of his power, with the Civil War nearly won. Clouds threatened another rainstorm. Then the strangest thing happened: The clouds parted and the sun burst out, flooding the spectacle. The president’s speech was brief — just 701 words.

“Fondly do we hope — fervently do we pray — that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away . . . With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan — to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”

(Previous page) The last photograph of Abraham Lincoln, taken by Samuel F. Warren on the White House balcony on March 6, 1865

On April 3, 1865, Richmond, Virginia, capital city of the Confederate States of America, fell to Union forces. Now it was only a matter of time before the war would finally be over. In the Union capital, emotions were high. The rebellion was almost over, and the victorious North held a celebration. Children ran through the streets waving littl

e paper flags that read WE CELEBRATE THE FALL OF RICHMOND. Across the country, people built bonfires, organized parades, fired guns, shot cannons, and sang patriotic songs.

The North rejoiced when the capital of the Confederacy, Richmond, fell onApril 3, 1865. This rare broadside celebrated the news but became obsoleteless than two weeks later when Lincoln was assassinated.

Four days later, John Wilkes Booth was drinking with a friend at a saloon on Houston Street in New York City. Booth struck the bar table with his fist and regretted a lost opportunity. “What an excellent chance I had, if I wished, to kill the president on Inauguration Day! I was on the stand, as close to him nearly as I am to you.”

Crushed by the fall of Richmond, the former rebel capital, John Wilkes Booth left New York City on April 8 and returned to Washington. The news there was terrible for him. On April 9, Confederate General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered to Union General Grant at Appomattox. Booth wandered the streets in despair.

On April 10, Abraham Lincoln appeared at a second-floor window of the Executive Mansion, as the White House was known then, to greet a crowd of citizens celebrating General Lee’s surrender. Lincoln did not have a prepared speech. He used humor to entertain the audience.

“I see that you have a band of music with you. . . . I have always thought ‘Dixie’ one of the best tunes I have ever heard. Our adversaries . . . attempted to appropriate it, but I insisted yesterday we fairly captured it. . . . I now request the band to favor me with its performance.”

On the night of April 11, a torchlight parade of a few thousand people, with bands and banners, assembled on the semicircular driveway in front of the Executive Mansion. This time, Lincoln delivered a long speech, without gloating over the Union victory. He intended to prepare the people for the long task of rebuilding the South. When someone in the crowd shouted that he couldn’t see the president, Lincoln’s son Tad volunteered to illuminate his father. When Lincoln dropped each page of his speech to the floor, it was Tad who scooped them up.

Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who organized the manhunt for John Wilkes Booth.

Lincoln continued: “We meet this evening, not in sorrow, but in gladness of heart.” He described recent events and gave credit to Union General Grant and his officers for the successful end to the war. He also discussed his desire that black people, especially those who had served in the Union army, be granted the right to vote.

As Lincoln spoke, one observer, Mrs. Lincoln’s dressmaker, Elizabeth Keckley, a free black woman, standing a few steps from the president, remarked that the lamplight made him “stand out boldly in the darkness.” The perfect target. “What an easy matter would it be to kill the president as he stands there! He could be shot down from the crowd,” she whispered, “and no one would be able to tell who fired the shot.”

In that crowd standing below Lincoln was John Wilkes Booth. He turned to his companion, David Herold, and objected to the idea that blacks and former slaves would become voting citizens. In the darkness, Booth threatened to kill Lincoln: “Now, by God, I’ll put him through.”

And as Booth left the White House grounds, he spoke to companion and co-conspirator Lewis Powell: “That is the last speech he will ever give.”

On the evening of April 13, Washington celebrated the end of the war with a grand illumination of the city. Public buildings and private homes glowed from candles, torches, gaslights, and fireworks. It was the most beautiful night in the history of the capital.

John Wilkes Booth saw all of this — the grand illumination, the crowds delirious with joy, the insults to the fallen Confederacy and her leaders. He returned to his room at the National Hotel after midnight. He could not sleep.

John Wilkes Booth awoke depressed. It was Good Friday morning, April 14, 1865. The Confederacy was dead. His cause was lost and his dreams of glory over. He did not know that this day, after enduring more than a week of bad news, he would enjoy a stunning reversal of fortune. No, all he knew this morning when he crawled out of bed was that he could not stand another day of Union victory celebrations.

Booth assumed that the day would unfold as the latest in a blur of days that had begun on April 3 when the Confederate capital, Richmond, fell to the Union. The very next day, the tyrant Abraham Lincoln had visited his captive prize and had the nerve to sit behind the desk occupied by the first and last president of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis. Then, on April 9, at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, General Robert E. Lee and his beloved Army of Northern Virginia surrendered. Two days later, Lincoln had made a speech proposing to give blacks the right to vote, and last night, April 13, all of Washington had celebrated with a grand illumination of the city. These days had been the worst of Booth’s young life.

Twenty-six years old, impossibly vain, an extremely talented actor, and a star member of a celebrated theatrical family, John Wilkes Booth was willing to throw away fame, wealth, and a promising future for the cause of the Confederacy. He was the son of the legendary actor Junius Brutus Booth and brother to Edwin Booth, one of the finest actors of his generation. Handsome and appealing, he was instantly recognizable to thousands of fans in both the North and South. His physical beauty astonished all who saw him. A fellow actor described his eyes as being “like living jewels.” Booth’s passions included fine clothing, Southern honor, good manners, beautiful women, and the romance of lost causes.

On April 14, Booth’s day began in the dining room of the National Hotel, where he ate breakfast. Around noon, he walked over to nearby Ford’s Theatre, a block from Pennsylvania Avenue, to pick up his mail: Ford’s customarily accepted personal mail as a courtesy to actors. There was a letter for Booth.

That same morning a letter arrived at the theater for someone else. There had been no time to mail it, so its sender, First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln, had used the president’s messenger to hand-deliver it to the owners of Ford’s Theatre. The mere arrival of the White House messenger told them that the president was coming to the theater tonight! Yes, the president and Mrs. Lincoln would attend this evening’s performance of the popular if silly comedy Our American Cousin. But the big news was that General Ulysses S. Grant was coming with them.

The Lincolns had given the Fords enough advance notice for the proprietors to decorate and join together the two theater boxes — seven and eight — that, by removal of a partition, formed the president’s box at the theater.

By the time Booth arrived at the theater, the president’s messenger had come and gone. Some time between noon and 12:30 P.M., as he sat on the top step in front of the entrance to Ford’s reading his letter, Booth heard the big news: In just eight hours, the man who was the subject of all his hating and plotting would stand on the very stone steps where he now sat. Here. Of all places, Lincoln was coming here.

Booth knew the layout of Ford’s intimately: the exact spot on Tenth Street where Lincoln would step out of his carriage, the box inside the theater where the president sat when he came to a performance, the route Lincoln could walk and the staircase he would climb to the box, the dark underground passageway beneath the stage. He knew the narrow hallway behind the stage where a back door opened to the alley and he knew how the president’s box hung directly above the stage.

Though Booth had never acted in Our American Cousin, he knew it well — its length, its scenes, its players and, most important, the number of actors onstage at any given moment during the performance. It was perfect. He would not have to hunt Lincoln. The president was coming to him.

(Previous page) An authentic Ford’s Theatre playbill for the night of April 14, 1865

He had only eight hours to prepare. If luck was on his side, there was just enough time to carry out his plan. Whoever told Booth about the president’s plan to attend the play that night had unknowingly activated in his mind an imaginary clock that began ticking down, minute by minut

e. He would have a busy afternoon.

Abraham Lincoln ate breakfast with his family and planned his day. The Lincolns’ eldest son, Robert, a junior officer of General Grant’s staff, was home from the war. Robert had been at the surrender at Appomattox, and his father was eager to hear the details. General Grant joined Lincoln’s cabinet meeting later that day where everyone in attendance, including Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, noticed Lincoln’s good mood. Secretary Welles, who kept a diary, wrote that Lincoln “had last night the usual dream which he had preceding nearly every great and important event of the War. . . . [Lincoln] said [the dream] related to . . . the water; that he seemed to be in some . . . indescribable vessel, and that was moving with great [speed] towards an indefinite shore. . . . [H]e had this dream preceding [the great battles of the Civil War].”

Lincoln had always believed in, and sometimes feared, the power of dreams. In 1863, while visiting Philadelphia, he sent an urgent telegram to Mary Todd Lincoln at the White House, warning of danger to their younger son: “Think you better put Tad’s pistol away. I had an ugly dream about him.”

After the cabinet meeting ended, the president followed his usual routine: receiving visits from friends and job seekers, reading his mail, and catching up on paperwork. He was eager to wind up business by 3:00 P.M. for an appointment he had with his wife, Mary. There was something he wanted to tell her.

At the theater, Henry Clay Ford wrote out the advertisement that appeared that afternoon in the Evening Star:

“LIEUT. GENERAL GRANT, PRESIDENT and Mrs. Lincoln have secured the State Box at Ford’s Theatre TO NIGHT, to witness Miss Laura Keene’s American Cousin.”

James Ford walked to the Treasury Department a few blocks away to borrow several flags to decorate the president’s box. On his way back, his arms wrapped around a bundle of brightly colored cotton and silk fabric, he bumped into Booth. They spoke briefly. Booth saw the red, white, and blue flags, further confirmation of the president’s visit that night.

Bloody Times: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Manhunt for Jefferson Davis

Bloody Times: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Manhunt for Jefferson Davis Bloody Crimes: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Chase for Jefferson Davis

Bloody Crimes: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Chase for Jefferson Davis Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer

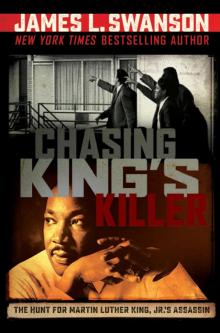

Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer Chasing King's Killer: The Hunt for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Assassin

Chasing King's Killer: The Hunt for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Assassin Bloody Crimes

Bloody Crimes End of Days

End of Days Chasing Lincoln's Killer

Chasing Lincoln's Killer Bloody Times

Bloody Times Manhunt

Manhunt Chasing King's Killer

Chasing King's Killer