- Home

- James L. Swanson

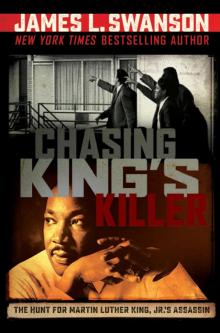

Chasing King's Killer: The Hunt for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Assassin Page 13

Chasing King's Killer: The Hunt for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Assassin Read online

Page 13

And so the troubled year of 1968 ended on a melancholy note of consolation and hope: “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.”

After the crew finished reading the remaining verses, Jim Lovell said farewell: “And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you—all of you on the good Earth.”

Americans turned their eyes skyward, and the marvels of what they saw there helped overcome some of the real pain and suffering on Earth by bringing together so many people in new shared wonder.

But how could the country and its people recover from the death of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.?

It is hard to believe that the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., happened half a century ago. In April 2018, America commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of his death. King had titled one of his books Where Do We Go from Here? Today, it seems fitting to ask, “Where have we come since then?”

If Martin Luther King had survived that day in Memphis, it is possible that, had he been given the gift of years, he might still be alive today. In April 2018, on the fiftieth anniversary of his assassination, Martin Luther King would have been eighty-nine years old.

If he were alive today, what would his message be?

He had won many of his most important battles. Yes, the old legal impediments of a nation that perpetuated racial segregation in education, housing, public transportation, restaurants, employment, and other areas of American life all came tumbling down. But that was not enough. There is more to civil rights than just overturning racist laws and passing new laws to protect those rights. One subject dear to King—economic justice—remains a major and hotly debated issue in our time. King would speak to us about it with passion and eloquence because he believed that true equality was not possible without economic opportunity and prosperity.

If he were alive today, Martin Luther King, Jr., would also speak about disparities in employment and criminal justice. New civil rights issues have arisen in our own time, including the Black Lives Matter movement, voter ID and voting rights concerns, and racially motivated shootings. King would be disappointed that, in many places and cultures around the world, the human and civil rights of many people—especially young girls and women—are violated every day. But he would have been amazed and delighted that in 2008, an African American had been elected president of the United States. That is part of King’s legacy, too.

In Washington, DC, you can visit memorials to three murdered American heroes. Abraham Lincoln sits in his marble columned memorial on the National Mall. John F. Kennedy’s eternal flame burns at his grave at Arlington Cemetery. And a new, monumental sculpture of Martin Luther King, Jr., larger than life, has risen to join them.

All were great men, all were inspirations in their own times, and remain so today. If you visit them at night when their memorials contrast dramatically against the dark sky, it is hard to forget Dr. King’s last wish, which Lincoln and Kennedy would have certainly shared: “Like anybody, I would like to live.”

And so their legacies live on: Lincoln, savior of a nation founded on a flawed experiment in liberty for some but not all, and who ended slavery but did not live long enough to guarantee the civil rights of the slaves he freed; Kennedy, who thought that racial oppression at home undermined America’s moral force on the world stage; and King, the prophet who sought to redeem America from the flawed, unjust, and violent century that followed the Civil War.

Perhaps you are also wondering what happened to some of the other people you have read about in this book.

In 1969, it was revealed that Robert F. Kennedy had authorized J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI wiretap surveillance of Dr. King. JET magazine, a leading African American publication, expressed the shock and disappointment felt throughout the black community. Kennedy was no longer alive to explain himself, and his reputation suffered.

On May 2, 1972, King’s old nemesis, J. Edgar Hoover, died peacefully in his sleep. He was seventy-seven years old, and he had been the director since 1935, for the entire existence of the FBI. He never repented his harassment of Martin Luther King, but he was proud of the outstanding work that his FBI had done in tracking down King’s assassin. At the agency he once ruled with an iron fist, Hoover had fallen from grace. Recently, the FBI office in New York City removed a wax figure of Hoover from public display and placed it in permanent storage.

On January 22, 1973, four years after he left the White House, President Lyndon B. Johnson died of a heart attack. He was sixty-four. He and King had not reconciled before King’s death. The wounds were too deep. But in LBJ’s last public remarks, given at a civil rights symposium at his presidential library shortly before he died, he must have had his old friend Martin in mind when he spoke the inspiring words from that great civil rights anthem: “We shall overcome.”

In 1974, six years after the assassination, Martin Luther King’s family suffered another tragedy. On the morning of Sunday, June 30, King’s sixty-nine-year-old mother, Alberta, was playing the organ at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church. A crazed twenty-three-year-old black man stormed in and opened fire with a pistol, hitting three people. He shot Alberta King in the head. Later, the attacker confessed that he had wanted to kill Martin Luther King’s father, but Mrs. King was closer and was an easier target, so he decided to shoot and kill her. The gunman also shot two more church members, killing one.

Reverand Martin Luther King, Sr., had lost both his son and his wife to assassins; it was more than any person should have to bear.

Meanwhile, James Earl Ray was restless behind bars. He did not want to spend the rest of his life in prison. He tried several times to escape but failed each time. In 1977, however, he succeeded, escaping from Tennessee’s Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary. But his freedom was short-lived. After his first prison escape in 1967, he had stayed on the run for more than a year. The FBI issued another reward poster; this time he was recaptured in just three days.

For the rest of his life, Ray sowed confusion and spread disinformation about the assassination. In 1978, he even testified before Congress, appearing before a joint committee. Ignoring the substantial evidence against him, Ray insisted that he had not killed King, and that the assassination was the work of a mysterious conspiracy in which he was only minimally involved. His lies deceived Dr. King’s family, and one of King’s sons visited Ray in prison, told him he believed him, and shook his hand. A disturbing photograph of their meeting depicts a reluctant Ray with his hands at his side, staring uncomfortably at the young Dexter King’s extended hand.

Ray gave interviews and wrote a book. Until the end, he denied that he was the assassin. James Earl Ray died on April 23, 1998. He was seventy years old, and he had outlived Martin Luther King by thirty years.

Ralph David Abernathy continued the good work of the civil rights movement. In 1989, he published his splendid autobiography, And the Walls Came Tumbling Down. No man had spent more time with Martin Luther King, knew him better, or loved him more. But Abernathy was criticized unfairly for portraying his old friend not falsely as a perfect saint but truthfully as a human being. Sadly, Abernathy died the next year, in 1990, at age sixty-four. He deserved more time, the kind of long life that his friend Martin had spoken about on April 3, 1968.

After King’s assassination, Coretta Scott King continued his work and helped lead the civil rights movement. She believed that women had important contributions to make. “Not enough attention,” she once said, “had been focused on the roles played by women in the struggle … women have been at the backbone of the whole civil rights movement.” In 1969, she published her memoirs, My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr., when her recollections were still fresh and her pain was

raw; her account of Martin’s death was heartbreaking. When former president Johnson died in 1973, Coretta attended his funeral—it was out of respect for the man who had once made history with her husband. She worked to have Martin’s birthday made the national holiday it is today. Coretta lived a full and active life, and she never remarried. She died in January 2006 at the age of seventy-eight. She had survived her husband by thirty-eight years.

Finally, in March 2015, a frail, forgotten, ninety-eight-year-old woman died at a nursing home in the Bronx, in New York City. She had been in the custody of mental institutions and care centers for decades. No friends or family ever came to visit her. Most people assumed she had died a long time ago. A journalist who found her shortly before her death learned that she had no recollection of the notorious event that had once made her infamous. Her conversation made little sense, but she had outlived them all. History had passed Izola Ware Curry by, for few people remembered how, fifty-seven years earlier on a fall day in Harlem, she had tried to assassinate Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and had almost ended this story before it ever began.

In the end, an assassin’s bullet could never erase what Martin Luther King achieved, or the legacy he created. But his death left behind a void. Jacqueline Kennedy, speaking of her murdered husband, once said, “Every man can make a difference, and every man should try.”

During his short life, Martin Luther King had tried to make a difference and he changed history. What else might he have accomplished if he had been around to help lead the civil rights movement into the 1970s, 1980s, or even today? Abraham Lincoln once spoke of his own “unfinished work.” If he had not been assassinated and had lived to heal the nation after the Civil War, America would have been a better place.

Like Lincoln, Martin Luther King summoned the nation to fulfill its promise of equal rights to all citizens. King’s all-too-brief life left much of his work undone, and his time was cut short before he could fulfill his potential. He was just thirty-nine years old, such a young man.

Today, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., is admired around the world as a great hero of our time. We can look back and speculate, but we will never know the ways in which his death altered the future course of American history. Yet we can be sure of one thing. Because of him, America is a better place, though still not fully what King hoped for and worked so hard to achieve.

He knew such changes would not come easily. King was all too aware of the sacrifices required. As he said prophetically in his last speech, “I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.” He had so many dreams. But he did not live to see them all come true.

And so King might ask us: Where do we go from here? How long will it take?

How long?

The spirit of the civil rights movement and of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., live on in many places, and there is no better time to visit them. We are at the dawn of civil rights tourism. Just as Americans visit the battlefields of the American Revolution and the Civil War, or the homes of the presidents like George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, or Abraham Lincoln’s modest frame house in Springfield, Illinois, the nation’s civil rights landmarks draw increasing numbers of visitors every year.

In Washington, DC, at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, you can visit a section of the famous lunch counter at the Woolworth’s Store in Greensboro, North Carolina, where four black college students were denied service when they refused to give up their seats and helped change history. This iconic relic looks just as it did on February 1, 1960, when it became the center of national attention. At the Lincoln Memorial, you can climb the stairs and stand on the exact spot where, during the March on Washington on August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. A stone block marks the spot. From there you can face the Washington Monument and enjoy the same view that Dr. King did on that historic day—and imagine the sea of hundreds of thousands of faces looking up and waiting for him and other key leaders to speak.

The Newseum on Pennsylvania Avenue has a fine exhibit on civil rights history that highlights not only Dr. King but also the other important leaders of the movement, and which includes the iron-barred door to the cell where King wrote his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” You can visit the Martin Luther King monument and the new Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, which includes exhibits on the history of the civil rights movement.

In Birmingham, Alabama, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church is a moving place of quiet pilgrimage. It was here, on September 15, 1963, that a bomb exploded during Sunday school, killing four little girls. The edifice serves as both a church and a museum where a clock, its hands still frozen in place, forever marks the time of the explosion. A visitor can stand on the very spot where the bomb blasted a hole through the brick wall of the church, and I remain haunted by my time there. It is easy to imagine the voice of Martin Luther King still echoing inside the church from the day he bade farewell to the “sweet princesses” who lost their lives there. In a striking juxtaposition, in a public park a few blocks away, a Confederate obelisk stands alongside monuments from America’s other wars.

In Atlanta, Martin Luther King’s home still stands, as does the spiritual and physical center of his ministry, Ebenezer Baptist Church. Also in Atlanta is the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, and it is there that he and his wife, Coretta Scott King, are buried.

In New York City, in Harlem, Blumstein’s department store, the place where Izola Curry attempted to end King’s life in 1958, closed long ago, but the building still stands as a ghostly landmark to an episode in King’s life that has been mostly forgotten.

In Memphis, Tennessee, the Lorraine Motel still stands, its famous colorful sign still inviting visitors. The Lorraine no longer accommodates overnight guests, but instead beckons daytime tourists on the civil rights trail. Like Ford’s Theatre in Washington, DC, and the Texas School Book Depository in Dallas, Texas, it is appropriate that the Lorraine has become a place of pilgrimage where Americans honor an assassinated hero. Today it is home to the National Civil Rights Museum. Once, some people wanted to tear down the Lorraine as an ugly reminder of a terrible tragedy. But more visionary voices prevailed, and it was preserved for history, and today teaches the lessons of the past to future generations.

It is easy to overlook the history right in front of our eyes. The history of the civil rights movement is all around you, in the living memories of those who participated in it. Many people alive today saw Martin Luther King, Jr., in person, or even met him. Some knew him well. Did anyone in your family participate in the civil rights movement? Ask your grandparents and great-grandparents, your aunts and uncles, and old family friends to share their recollections of those times. What was it like to be part of a great social movement? Where were they the day they learned that Martin Luther King was dead? In basements and attics all across America, perhaps even in your own home, documents and relics from the movement—picket signs, posters, photographs, souvenirs, event programs, pin-back buttons, and more—have been hidden away for decades. These things should be rediscovered, cherished, and preserved. Interview family members and friends, or ask them to write down their recollections. History dies forever unless those living today work to pass it on to future generations.

First bill introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives four days after King’s death in 1968 by Rep. John Conyers (D-MI).

96TH CONGRESS (1979–1980)

U.S. Senate. Martin Luther King, Jr., National Holiday Bill (S. 25). Joint Hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee, the House Post Office and Civil Service Committee. 96th Congress, 1st Session, March 27 and June 21, 1979. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1979.

S.25, a bill to designate the birthday of Martin Luther King Junior a legal public holiday. Reported to the Senate from the Committee on Judiciary, Senate Report

96-284, August 1, 1979.

H.R. 5461, a bill to designate the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., a legal public holiday. Reported from the House Post Office and Civil Service Committee, House Report 97-543, October 23, 1979.

H.R. 5461, failed passage in the House of Representatives under suspension of the rules, 252 ayes to 133 noes, November 13, 1979.

97TH CONGRESS (1981–1982)

U.S. House of Representatives. Martin Luther King, Jr., Holiday Bill. (H.R. 800). Hearings before the Subcommittee on Census and Population of the House Post Office and Civil Service Committee. 97th Congress, 2nd Session, February 23, 1982. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1982.

98TH CONGRESS (1983–1984)

U.S. House of Representatives. Martin Luther King, Jr., Holiday Bill. (H.R. 800) Hearings before the Subcommittee on Census and Statistics of the House Post Office and Civil Service Committee. 98th Congress, 1st Session. June 7, 1983. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1983.

H.R. 3345, as reported to the House of Representatives. House Report 98-314 on July 26, 1983.

H.R. 3706, as passed by the House of Representatives under suspension of the rules, by a vote of 338 ayes to 90 noes on August 2, 1983, and as passed by the Senate by a vote of 78 ayes to 22 noes on October 19, 1983.

Public Law 98-144, signed by President Reagan on November 2, 1983. (Observance every third Monday in January, beginning 1986.)

Bloody Times: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Manhunt for Jefferson Davis

Bloody Times: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Manhunt for Jefferson Davis Bloody Crimes: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Chase for Jefferson Davis

Bloody Crimes: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Chase for Jefferson Davis Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer

Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer Chasing King's Killer: The Hunt for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Assassin

Chasing King's Killer: The Hunt for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Assassin Bloody Crimes

Bloody Crimes End of Days

End of Days Chasing Lincoln's Killer

Chasing Lincoln's Killer Bloody Times

Bloody Times Manhunt

Manhunt Chasing King's Killer

Chasing King's Killer